How to Collect Quality Drone Data – Part 4: Long Corridors

In Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of this series, we learned how to capture pretty much any bare earth site, adapting to significant elevation changes, faces, and overhangs. In terms of terrain capture, there isn’t really anything you can’t tackle with this knowledge.

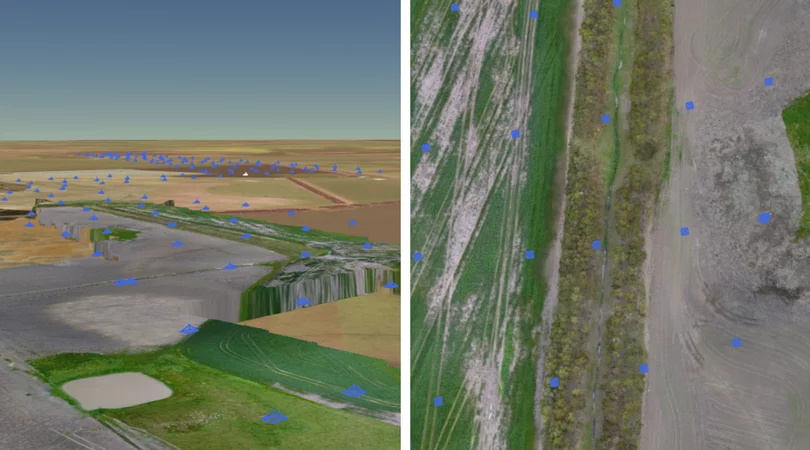

That said, if we want to capture long corridors such as roads, train lines, drainage channels, and pipes, there are a few more things we need to consider.

One approach would be to put a huge rectangle around the area and fly it as per usual. For small sections this may be fine. However, if you’re capturing miles of terrain, you’ll end up with enormous datasets with lots of unnecessary data. So make it thinner, right? Yes, but how thin is too thin?

Then there’s ground control. We know that ground control points (GCPs) are the key to accurate drone data, but we usually put them around the perimeter (horizontally and vertically) and in the middle. What do you do for a road?

So the questions we need to answer are:

- Where should I put my ground control points (GCPs)?

- How thin can I make it?

- How much does each run need to overlap with the rest?

Ground Control Placement

The first thing you need to consider when you get to site is where to place your GCPs, particularly if you’re using AeroPoints because the longer you can leave them out the better.

First, the more the merrier when it comes to ground control. You should never be trying to use the bare minimum, just in case there are any issues with any of them. If you have a set of AeroPoints, always use all of them.

We’ve conducted a few tests, and this is what we’ve learned:

- Ensure that every GCP is visible in at least five photos

This means that you do not want to have them near the edges of the images, you want them where they’ll have lots of photos taken of them.

- “Ladder” your GCPs

Place a GCP on each side of the corridor at least every 500ft (150m), covering all extents of the survey.

Flight Planning

As always, the way you capture the data is just as important as the ground control and we’ve had a good look at this as well.

The most common mistake is not having enough runs along the width of the corridor. Photogrammetry works by having multiple images of the same features from known positions so their locations can be triangulated and built into a 3D model. If there are only a few photos along the width of the corridor, it’s highly unlikely that anyone will be able to stitch it into a usable model.

With that in mind, here are our guidelines for effectively capturing long thin corridors:

- Minimum of four runs up and down the length of the area.

- Increase the side-lap and/or reduce the flight height.

- Ensure that there is sufficient overlap between flight patterns.

You’ll often need to fly chunks of the corridor separately to follow the shape of the corridor. When this happens, ensure that you have sufficient overlap between flights so they can be stitched together.

Four to five rows of overlap should be sufficient.

To be continued . . .